Walter Siti

Tattoos

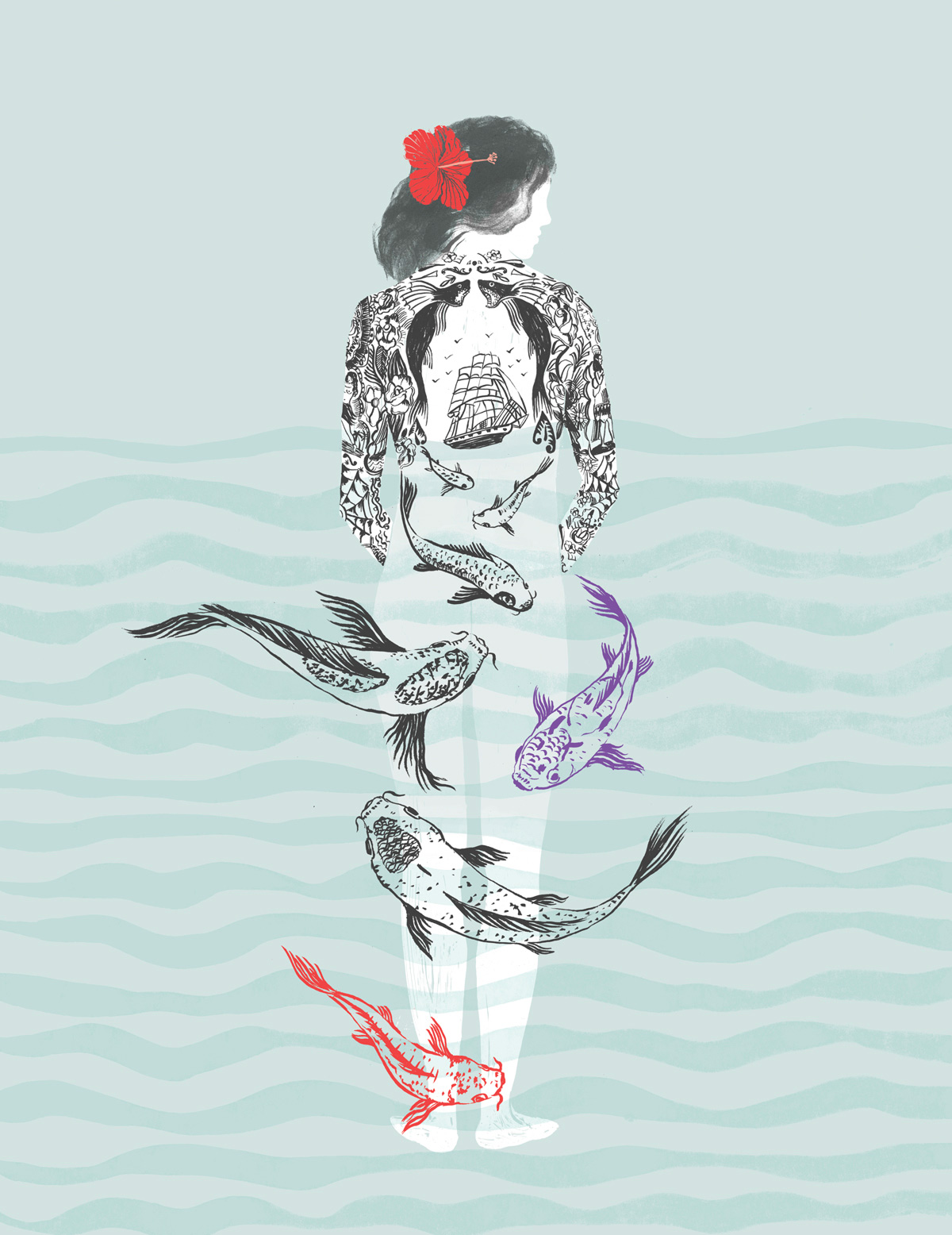

DISCIPLES OF SAINT BARTHOLOMEW

Why don’t animals feel the need to wear clothes? Why is the sight of dogs in little middle-class coats so unnatural that it’s heart wrenching? A horse’s trappings reflect its owner’s pride; circus monkeys are a parody of ourselves. All an animal needs is its hide, its fur, its feathers, or its scales, for it does not care if it is being looked at. In Italo Calvino’s The Watcher, the protagonist—an election clerk at a poll station inside the Cottolengo hospital in Turin—observes voters’ IDs, as required by his job, and their photographs, noticing that the only ones who come out well are nuns, which triggers a mental comparison with cats—who are also always photogenic—and he comes to the conclusion that both categories look good in pictures because they are the only ones who don’t pose for them. Adam and Eve didn’t feel naked until after they had eaten the fruit of the tree of knowledge, and God knew straight away: “Who told you that you were naked? Did you eat the fruit of the tree I had forbidden you to eat?” They were naked before God’s eye, so God took pity, and before he banished them from Eden, he replaced the thrown- together fig leaves with tunics made from animal skins. (Scripture doesn’t tell us where he got the skins: was death already present in Eden? Or did He have other animals available outside the garden that could be killed and skinned? Were these synthetic skins?) Those who truly believe in God and trust in his Providence do not need clothes. Do not trouble yourselves with clothing, Jesus preached in the same episode in which he taught his disciples the Lord’s Prayer, look at the splendid natural liveries of the birds of the air and the lilies of the fields, and yet they neither toil nor spin. Saint Francis shed his clothes in public, and if he could, he would have gone around naked (he couldn’t because of original sin); however, he did request to be buried naked after his death. Unsaintly human knowledge is awareness of being observed by others.

Illustrator Elisa Talentino

Animals may sometimes wear a disguise, but only on special occasions: they try to look like a tree trunk, a coral, they pretend they are larger, or display a fan of multicolored feathers; certain butterflies mimic a bird of prey’s menacing yellow irises with their wings. They do so to protect themselves, to disappear, to seduce, or to instill fear. A tattoo is both more and less than a piece of clothing: most often it is permanent, but it offers no protection from blows or bad weather. Like body painting, it can conceal nudity (unless it is intended to emphasize it); it is more symbolic and more democratic than clothing, even the most extravagant designs are available to the middle classes. Tattoos are as ancient as civilization—Ötzi, the Iceman who lived over 5000 years ago, had simple cross-shaped marks tattooed in spots that correspond almost exactly with those used in Chinese acupuncture. Most likely their purpose was therapeutic; paleoanthropologists believe that other similarly antique tattoos held a ritual function, representing rites of passage. Throughout history, there have been devotional tattoos (a Coptic cross on the wrist) and ones inspired by military camaraderie (like those worn by sailors); to this day, in Borneo and the Amazon, tattoos show a person’s belonging to a group or their marital status. Beginning with the Greeks, the West has generally considered tattoos a mark of savagery: Parian marble statues represent the body in its purity (a way of thinking that carried over to Kim Kardashian, “Honey, would you put a bumper sticker on a Bentley?”). According to Cesare Lombroso (and to Donald Trump), tattoos were (are) a symptom of deviance; in the small town where I grew up, even in the Fifties, if you saw someone with a tattoo, you thought they must have been in prison. Children play with fake tattoos—crushed flower petals or more modern chemical products that come off with makeup remover.

The childish regression of contemporary Western culture—or a dark desire for powerless savagery—is causing the more conspicuous phenomenon of mass tattooing. Nowadays, in downtown Milan, it’s almost more likely to meet a young tattooed man (or woman—as a matter of fact, the proportional increase of the female quota is the real phenomenon inside the phenomenon), than one whose skin bears no writing or drawings. As for myself, pushing eighty and raised on hermeneutics, when I encounter one of these people, I can’t help but ask myself what they “want to tell me” with their tattoos, what the non- verbal discourse is here. The muscular men I would see at the gym in Rome twenty or so years ago had Gott mit Uns inscribed on their backs, they boxed and practiced valetudo, their tattoos meant that they wished to be perceived as fearless legionaries. However, there has been a mutation. This anthropologic type is now a minority, their female friends and partners often have more tattoos than they do, and above all, mass dissemination has dulled if not entirely suppressed political distinctions. Possibly, decoration prevails over meaning, but this is exactly why the latent significance is worth pursuing; and we must not stop at the first answers tattooed people offer when you ask them, “why do you do it?”. The majority will tell you that its purpose is to mark an achievement, or to remember a promise made to themselves, or a dedication to a loved one (“forever yours”); or, cutting short, because it is their passion, “for the beauty of it” or “because I like myself this way.” Yet, if one digs a bit deeper, beyond functionality and personal taste, the unuttered—and sociologically interesting—answers emerge.

The old and wise “know yourself” has been replaced by an egocentric “express yourself”.

As if the body were no longer sufficient in itself, but were forced to become a palette, a blackboard, a billboard; identity is a trap, the old and wise “know yourself” has been replaced by an egocentric “express yourself.” People get tattoos so they will be seen, but also to camouflage themselves: nowadays, expressing oneself is to present oneself as an individual in a society that only recognizes those who do not conform, who are “non-conforming, like everyone else”—in this season of mass individualism, having an identity means finding a pigeonhole from which to state with conviction “I do not want to be pigeonholed.” Absolute diversity is not acknowledged, and thus it is as if it did not exist: being unique only makes sense if uniqueness is assimilated—it is fashionable to be oneself. In pornography— supposedly the reign of nakedness par excellence—tattooed bodies with more or less explicit inscriptions (“freedom, curious, patior, fuck me”) are proliferating. This phenomenon parallels the increasingly common habit—in porn movies—of filming oneself with a phone while having sex so as to offer viewers two simultaneous points of view: a closeup and a long shot. I fear this habit has spread to what we insist on calling the “real” world: sex as a performance is nothing but the corollary of a whole society in which the most active role accorded to an individual is to be a viewer of oneself.

Tattoos have made their way into the most secret recesses of the body, where the eye is not supposed to reach: the anal area, around the vagina. Etymologically speaking, the obscene is that which cannot be represented on the scene; the end of obscenity is when that which should be censured becomes a hype. Nudity no longer fears the gaze for it has become hyper-nudity, a cataphract of imagination. Tattooing these areas is painful, too, like tattooing one’s Adam’s apple or cornea; it is a test of courage, and for women it represents the pride of female empowerment. Tattoos often go hand in hand with piercings— their purpose is to make parents and puritans fret (though now there are parents getting their daughters their first tattoo for their eighteenth birthday, and thoroughly tattooed rappers getting all sentimental on Mother’s Day). It is a well-known fact that nowadays the real transgression is tenderness.

Your body is your calling card: a proliferation of tattoos can serve as a simplified autobiography, as dermal emojis, of sorts. The writing is basic, banal statements in exotic alphabets, the paintings also stereotypical—increasingly frequent are completely black arms and legs. The dyslexia growing among young people is turning into post-lexia, a hankering for a language that is no longer verbal. My body speaks for me. As the body inevitably wilts, many start wishing they could remove these tattoos, but it’s not that easy: even laser therapy can leave whitish marks. We wish to hand ourselves over to death naked, but it’s too late; tattooed bodies are prisoners of communication (that blessed “communication” that has replaced knowledge). Tattoos are rendering the modern Adams and Eves accustomed to communicate without saying a word, for they have accepted to wear a suit no longer made of animal skins (of course, we’re too eco-friendly for that), but rather their own skin reduced to a confused and resigned babel. In the Last Judgement painted by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel in his later years, just below the Savior and to His right is Saint Bartholomew: his martyrdom, as is common knowledge, was to be skinned alive, and the artist imagined him displaying his own limp skin like an empty bag. Tradition has it that Michelangelo depicted his own self-portrait in the visage still outlined in the skin—an involuntary, prophetic tattoo, the remnants of a heroic act of faith, as well as a fierce judgement upon himself: it could, today, be chosen as an icon of a civilization that crushes bodies and minds, turning them into the raw materials of the economy.